Finding My Voice

Jigna Rao was familiar with pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) in her native India, but had never heard of pelvic TB, a type of extrapulmonary TB disease that affects women. Pelvic TB often produces no symptoms even as it advances and affects internal organs, including the reproductive system. Asymptomatic pelvic TB may go undetected for 10 to 20 years until is discovered, typically in the course of assessing complaints of infertility. This was true in Jigna's case.

Jigna Rao was familiar with pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) in her native India, but had never heard of pelvic TB, a type of extrapulmonary TB disease that affects women. Pelvic TB often produces no symptoms even as it advances and affects internal organs, including the reproductive system. Asymptomatic pelvic TB may go undetected for 10 to 20 years until is discovered, typically in the course of assessing complaints of infertility. This was true in Jigna's case.

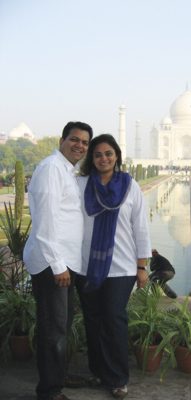

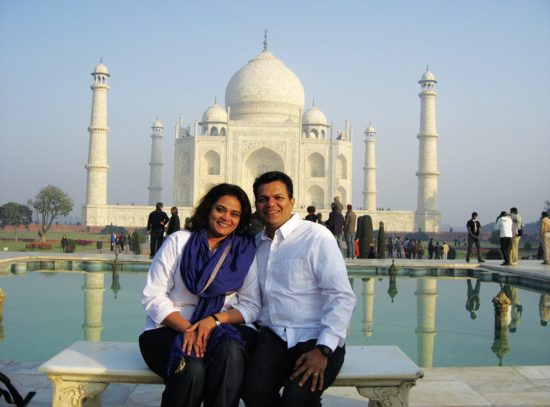

Jigna and her husband were recently established in the US and were ready to start a family. After months of trying on their own without a favorable outcome they decided to consult with an infertility specialist, who put her on an infertility treatment plan. A long series of painful and invasive treatments resulted in failures, Jigna and her husband decided to consult with another specialist who agreed with Jigna that instead of a treatment plan, there was an immediate need to investigate the reason for Jigna's infertility and then develop a plan around it. This resulted in exploratory surgery and, eventually, a diagnosis of pelvic TB.

Jigna immediately began treatment for TB and made a full recovery from the disease, but the experience changed her life. She had to give up her dreams of motherhood and accept that she would not become pregnant. Moreover, she experienced how stigma associated with TB can increase patients' sense of loneliness and isolation, making it more difficult to reach out for the knowledge and support needed for good treatment outcomes. After she finished her TB treatment she started to look for ways to use her own experience to help TB patients, their loved ones, and their healthcare providers in the struggle against the disease. This special World TB Day issue of Notes from the Field highlights Jigna Rao's experience of TB diagnosis and treatment, and describes how she uses the lessons learned inthat experience to highlight the effects of TB disease on a patient and her efforts to share her experience with medical professionals in order to raise their level of awareness. This issue is the first in a two-part series focusing on TB patient advocacy and empowerment. The second part will be available later this year.

Learning about TB, Learning about Stigma

Every case of TB is unique, but shock upon hearingthe diagnosis is common for people in the United States (US). Even those of us who come from countries where TB is prevalent tend to think it would never affect us or our families, especially when we are settled in the US. My husband and I were completely unprepared to learn that TB was at the root of our struggle with infertility. I had hardly been sick for more than a few days in the several years since we arrived in the US six years earlier! Being asymptomatic made it harder for me to fully accept the diagnosis. Only after reviewing test results and images with my doctors did I stop feeling it could not possibly be true that I had TB.Educating me on extrapulmonary TB was a challenge for my doctors, since they had very little experience with it themselves. I called my former gynecologist in Mumbai to see if I could learn anything more. I was surprised when she told me that pelvic TB is not uncommon in much of Southeast Asia, and that it is routinely considered as a cause of infertility.

Growing up in Mumbai I never saw an anti-TB public health campaign featuring people who looked like my middle class family. I never knew of anyone in our high-rise apartment building being sick with TB. Like my family and friends, I strongly associated TB with impoverished communities and environments where people lacked sanitation, adequate shelter, and food. Somehow we believed TB was confined to those environments and had no power to infect people in neighborhoods like ours. As I began to emerge from denial about my diagnosis I realized we associated TB with more than physical weakness and uncleanliness. Even though we had a basic understanding of how TB is spread and survives within a human host, we shared an unspoken sense that people who developed TB disease must also have some moral failure, vices, or a wicked lifestyle. TB happened to other people, who we would have described as alien and somehow "less" than us.

Awareness of TB-related stigma hit me hard and I was trying to come to terms with the reality that TB would leave me infertile. The family my husband andI planned on was an important part of my identity, and it seemed to crumble before this disease. As I began to tell family and friends of my diagnosis, I saw that many of them shared my unspoken belief that only people with moral failures succumb to TB. Their facial expressions and body language changed, sometimes very subtly and sometimes in ways that were impossible to ignore. Some people abruptly ended a conversation with me when I spoke of the

diagnosis. With others, just the look in their eye let me know that as a person with TB, I had

become less valued in their eyes.

Worried about how people we knew here in the US and back in India would react, some well-meaning

family members counseled me not to speak about my diagnosis. I knew that my talking about TB

affected their social standing – in our culture as well as others, the stigma of TB affects not

only the patient but the entire family.

The feeling that I had something to hide, that TB was not something I could talk openly about, was

hurtful and left me feeling emotionally isolated. I understood why people go to great lengths to

hide the disease, even to the point of avoiding clinics or public

health officials associated with TB.

The Power of Social Support

Fortunately, those nearest to me reacted differently. My husband and several family members threw themselves into supporting me throughout treatment, studying the little information I gathered on pelvic TB, helping me search the internet for others who were undergoing the same treatment, and sometimes talking about anything but TB to make me laugh, think of a bright future, and forget the worries of treatment for a while. For all my searching I could not find a formal or informal patient support network, either in the state where I live or online. Daily calls from family members and my husband's constant support kept me going through the many months of treatment. I was also fortunate to have a great support system at work, which was very important. It allowed me to continue to build my self-confidence while I struggled to find new meaning in my personal life.

Fortunately, those nearest to me reacted differently. My husband and several family members threw themselves into supporting me throughout treatment, studying the little information I gathered on pelvic TB, helping me search the internet for others who were undergoing the same treatment, and sometimes talking about anything but TB to make me laugh, think of a bright future, and forget the worries of treatment for a while. For all my searching I could not find a formal or informal patient support network, either in the state where I live or online. Daily calls from family members and my husband's constant support kept me going through the many months of treatment. I was also fortunate to have a great support system at work, which was very important. It allowed me to continue to build my self-confidence while I struggled to find new meaning in my personal life.

From Acceptance to Advocacy

When I completed treatment and my doctors declared me completely recovered from TB, I began to reconstruct my life. I restarted my career along new lines, developed new hobbies, and made new friendships. My husband and I had to rethink how we would create the family we so wanted. This process helped me to accept the permanent consequences of pelvic TB and think about a new future, one different than I had always imagined, but full of its own promise.

But my experience with TB never completely left me. I was left newly sensitized to the emotional dimensions of illness and how lonely and isolating the experience of disease can be, especially when one's disease is unfamiliar to healthcare providers in a particular setting, as was my experience being treated for pelvic TB in the US.

With these issues always in my thoughts, I was pleased when a journalist asked to interview me for a newspaper article highlighting the challenges of extrapulmonary TB and the long-term consequences of pelvic TB. I was eager and a bit anxious to read thearticle, and I was up early waiting for the morning edition of the newspaper as soon as it came out. But I was not prepared for the impact of seeing my story in print. So much of the experience came back in an emotional rush that I could hardly move after reading it. At the same time, realizing that someone had thought my experience was important enough to develop an article and print it for others to learn from gave me a sense of empowerment.

I began to seek out opportunities to share the article and eventually, to speak to others about my experience. I was invited to talk to healthcare professionals about atypical manifestations of TB. This allowed me to share insights into what patients go through when they are diagnosed with TB and how healthcare providers can help patients respond more effectively to the emotional challenges of the disease. It was gratifying to feel like my experience was useful to providers and helped them to develop more effective relationships with patients.

Even more important to me were conversations with TB patients. When I had TB, I knew no one who was like me and had a similar experience. Not having anyone around who shared my experience contributed

to my sense of isolation. Every time I sat down with a patient to talk about what to expect from TB

treatment, answer questions, sympathize, and provide living proof that there is life after TB, I

felt a little stronger. I could see that talking with me was positive for patients, and knowing

that my ordeal with TB had been useful for someone else meant the experience had constructive

outcomes, not solely negative consequences for my life.

My contacts with healthcare providers around TB eventually led me to a diverse group of physicians,

academics, and activists dedicated to promoting health and wellness in South Asian immigrants,

through

community education, innovative programs, and research. Working with this group I learned that my challenges with TB diagnosis and treatment– conditions that are rare in the US and consequently unfamiliar to doctors, the negative impact of

stigma, and the lack of opportunities to network with other patients from similar backgrounds -

were common to immigrant groups in the US facing all kinds of illnesses and health needs.

Now I collaborate with healthcare providers and other community members to develop strategies to

overcome these challenges and more generally to create culturally informed approaches to patient

care. The more I speak on these issues in community forums and at regional and national meetings, I

see more clearly the power of bringing patients and communities into the healthcare team to

establish health care that fosters mutual understanding between providers and patients and is truly

responsive to the needs of increasingly

diverse communities.

Extrapulmonary TB

Extrapulmonary TB is tuberculosis in parts of the body other than the lungs. The symptoms of extrapulmonary TB are different from pulmonary TB, so diagnosis may be delayed (Gonzalez, et al.,

2003). Clinicians may also be unfamiliar with the symptoms of extrapulmonary TB, which can lead to

delayed diagnosis or misdiagnosis.

In general, extrapulmonary TB is more commonly diagnosed among patients who are female, younger,

and HIV-infected. Other factors associated with extrapulmonary TB include race/ethnicity,

homelessness, drug use, and long-term care facilities (Yang, et al., 2004).

Types of extrapulmonary TB may differ by geography and ethnicity. In the US, extrapulmonary TB is

often associated with ethnic minorities and foreign-born immigrants (Rieder, et al., 1990).

Extrapulmonary TB is more common among Southeast Asian immigrants than among other immigrants

and US natives (Asghar et al., 2008).

Confronting Stigma

Negative reactions from others who learn of a TB diagnosis can compound the physical impact of TB disease and the social impact of necessary

isolation for pulmonary TB patients. Fear that TB- associated stigma will outlast the course of the

disease and permanently damage one's social identity adds layers of emotional distress, grief, even

depression, to the experience of TB.

Healthcare providers typically address the impact of TB-related stigma with education to highlight

that TB is transmitted through the air, not genetic, and fully curable. Education can calm

patients' fears that TB disease results from physical or moral failings and will inevitably have devastating consequences. However, it does not

directly speak to cultural-specific ways patients, their friends and family, and others react to a

TB diagnosis.

Stigma may be more effectively addressed by individuals who share a patient's cultural and ethnic

identity and can respond in culturally meaningful ways. Support from members of patient's family

and social networks demonstrates the patient is still valued. Public statements against

stigmatizing attitudes and practices from highly respected or influential figures can also weaken

the power of stigma throughout all levels

of society.

Challenging the Stigma of TB

"Among all the activities I do now to promote healthcare of South Asians living in the US, communicating with other people affected by TB

remains uniquely powerful. It goes beyond the immediate connection and support we feel as patients

who have been through similar struggles with a devastating disease. As we convey our stories to a

wide audience of healthcare providers, community members, and policy makers we are creating a new,

more fully human face of TB. The face that emerges from our stories is the face of people like me,

other immigrants, and Americans from all walks of life. Our portrayal of the disease is

recognizable to communities everywhere and serves to weaken the power of stigmatized images of TB

sufferers as alien and

inferior to the rest of us." - Jigna Rao

Advocacy in the Global Struggle against TB

From low-incidence countries like the US to parts of the world where TB is endemic, advocacy plays

a key role in getting support for TB programs and ensuring optimal patient outcomes. The goal of advocacy is

to promote solutions to problems as well as to raise public and official awareness of problems. TB

advocacy involves the dissemination of information and other strategies to influence policy

development and implementation,

public opinion, service provisions, and communities and individuals affected by TB. Advocacy

efforts can range from the personal to the political. Whether a patient engages in their own health

care, joins a support group, becomes a peer advocate, writes letters to elected officials or

lobbies for issues, they are advocating for themselves and other TB patients.

The World Health Organization houses the Stop TB Partnership, which recognizes advocacy as

essential to its overall mission of TB elimination through high-quality care and treatment and

effective control strategies. Advocacy mobilizes diverse social, scientific, health systems, and

political partners by emphasizing their common interest in TB elimination, thus strengthening the

foundation of global efforts against the disease.

Advocacy is also a powerful tool to improve patient care when an advocate works one-on-one with patients to provide health-related education, identify needed services, or to improve communication

between providers and the patients. Patient advocacy may be informal, as when Jigna responded to a

provider's request that she speak to a TB patient about her own experience. However, advocates can also be

fully incorporated in healthcare teams to improve coordination of care. Advocates who support

patients through each step of chronic or long-term treatment are increasingly seen as valuable

members of healthcare teams in HIV, cancer, diabetes, and other conditions (Webel, Okonsky,

Trompeta, & Holzemer, 2010).

In addition to their direct interaction with patients, advocates can strengthen the healthcare

team's capacity to provide patient-centered care. When they are incorporated into the healthcare

team, patient advocates provide valuable feedback on how patients experience diagnosis, illness,

and treatment, which helps providers better respond to patient needs. This feedback is especially

valuable when treating conditions common in populations that providers are less familiar with.

Advocates like Jigna who are from growing immigrant communities in the US can help providers

develop their competency to work effectively with those populations.

When, like Jigna, an advocate has been through the experience of TB diagnosis treatment, he or she

can also act as a role model for other patients to become full partners in their treatment plan.

This dimension of advocacy is particularly

important in conditions like

TB disease, in which cultural and social forces can impose stigma on patients and increase their

sense of isolation and vulnerability (DiMatteo,

2004). Advocates who as former patients are respected and valued by other members of the TB

healthcare team provide compelling evidence that the disease does not

diminish the social worth of

people whom it affects.

Resources for Advocacy

People with TB, members of communities affected by the disease, and healthcare professionals can

engage in various activities to strengthen global, regional, national, and local responses to TB.

Advocacy to Control TB Internationally (Action) http://www.action.org/ offers resources and

guidance for advocacy, in addition to news and information about TB and related conditions.

The resources of the Stop TB Partnership http://www.stoptb.org/ includes an Advocacy Network

listserv, which you can sign up for at http://www.stoptb.org/getinvolved/resmob/signup.asp

Empowered patients are healthcare providers' most powerful ally in treating TB and preventing its

spread. Patients can become empowered by learning their rights and speaking with other TB patients.

The World Health Organization has endorsed the Patient's Charter for Tuberculosis Care: Patient's

Rights and Responsibilities, which defines patients' essential role in high quality care,

mobilizing community support for TB services, and building political and health systems capacity to

meet the challenge of TB control and elimination.

http://www.who.int/tb/publications/2006/istc_charter.pdf

Although online patient communities providing mutual support during and after treatment are not as

common in TB as other conditions, individuals increasingly share their experience and respond to

others' stories through blogs related to

TB treatment. Doctors without Borders hosts an interactive blog project with contributions from

patients with multidrug- resistant TB all over the world, the TB & Me blog.

http://msf.ca/blogs/tb/tag/support/?gclid=CI-8k4CQ7q0CFcnc4AodbD-m6Q

Outside the field of TB control and elimination many resources exist related to patient advocacy,

including some developed for specific diseases such as cancer.

Side-Out Foundation

http://www.side-out.org/cancer-resources/how-to-be-an-advocate/medical-advocacy/

Finally, there are

many resources related to general healthcare advocacy.

Tools and education from the US department of Health and Human Services include

http://www.ahrq.gov/questions/

Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation's Advocacy toolkit:

http://www.christopherreeve.org/atf/cf/%7B3d83418f-b967-4c18-8ada-adc2e5355071%7D/ADVOCACYTOOLKITRF311B.PDF

The guide "Being a Healthy Adult: How to Advocate for Your Health and Health Care" from The

Elizabeth M. Boggs Center for Developmental Disabilities at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey http://rwjms.umdnj.edu/boggscenter/products/documents/TransitiontoAdultHealthcare-EN-complete.pdf

Work Cited

Asghar, RJ, pratt, RH, Kammerer, JS and Navin, TR, Tuberculosis in South Asians Living in the United States, 1993-2004. Arch Intern Med. 2008 168(9):936-943.

DiMatteo, R. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: a meta-analysis. Health Psych 2004 23(2), 207-218.

gonzalez O Y, Adams G, Teeter LD, Bui, TT Musser, JM and Graviss, EA. Extra-pulmonary manifestations in a large metropolitan area with a low incidence of tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2003; 7: 1178-1185. Accessed 1/17/12

Lin, JN, Lai, CH, Chen, YH, lee, SSJ, Tsai, SS, Huang, CK, Chung, HC, Liang, SH and Lin, HH. Risk Factors for Extra-pulmonary Tuberculosis Compared to Pulmonary Tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009; 13(5):620-625. Accessed 1/19/12

Rieder HL, Snider DH Jr., Cauthen GM. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis in the United States. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990; 141:347-51

Webel, A. R., Okonsky, J., Trompeta, J., & Holzemer, W. L. A systematic review of the effectiveness of peer-based interventions on health-related behaviors in adults. Am J Public Health 2010, 100(2), 247-253.

Yang, Z, Kong, Y, Wilson, F, Foxman, B, Folwer, AH, Marrs, CF, Cave MD and Bates, JH. Identification of Risk Factors for Extrapulmonary Tuberculosis. Clinical Infectious Disease 2004; 38:199-205. Accessed 1/17/12

Let Us Highlight your Case

Have you, or a colleague faced a TB case that was challenging due to your patient's cultural beliefs or practices being dissimilar from your own? Have you experienced success in a case because you changed your typical approach based on something you learned about the patient's culture? If so, we'd love to highlight your case in an upcoming issue. Don't worry about producing a polished piece – we do most of the work! Please contact Jennifer at campbejk@umdnj.edu if you have some ideas.